NOTE: All historical facts recounted here were taken (but reworded by this author) from the “William Randolph Hearst” and “Hearst Castle” articles at en.m.wikipedia.org. The feature aerial photo was downloaded from the internet as it was uncopyrighted.

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (1863-1951) was born into a wealthy family in San Francisco. George Hearst, his father, was a self-made millionaire, politician, and patriarch of the Hearst business dynasty. Founder of many mining operations, George developed and expanded in the late 1870’s the Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota eventually making it into what was to become the deepest and largest gold mine in North America. The mine was listed on the NYSE in 1879 and profits from it and his other mine holdings left George worth $19 M (equivalent to $644 M in 2021) when he died in 1891. As an only child, William inherited much of his father’s fortune subsequently through his mother, Phoebe Apperson Hearst. That inheritance included the newspaper, San Francisco Examiner, which his father acquired in 1880 as payment for a gambling debt. The young William had been looking for a career occupation after being kicked out of Havard, and this was it. He invested heavily in the publication business; purchased state-of-the-art printing equipment; and hired top journalists, editors, and staff to build a nation-wide empire that by the 1920’s consisted of twenty-eight newspapers, thirteen magazines, eight radio stations, four film studios, and employed 31,000 people.

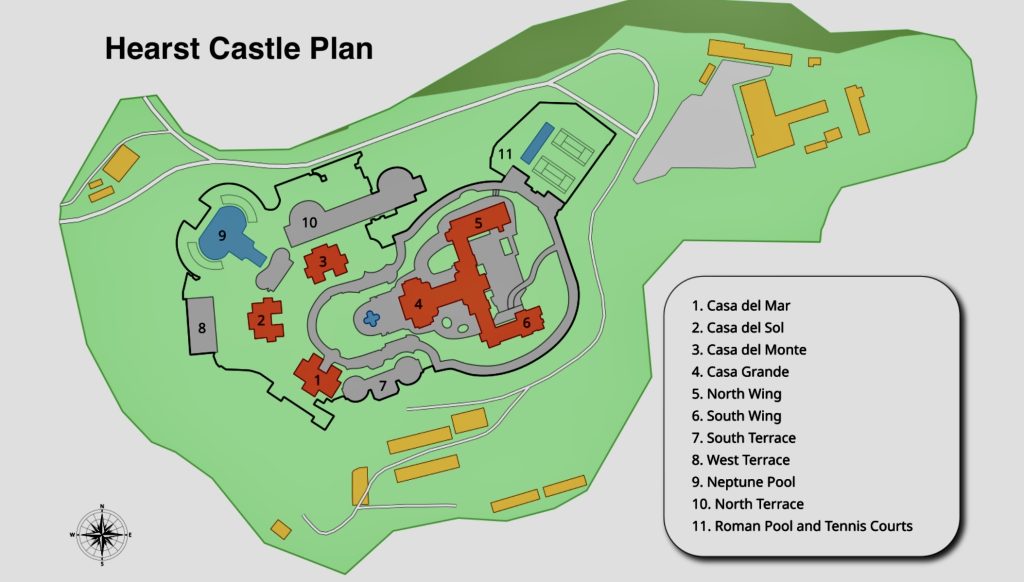

George Hearst used some of his mining fortune to buy land along California’s central coast. In 1865, he bought 30,000 acres (part of Rancho Piedra Blanca) and all 13,184 acres of Rancho Santa Rosa. This combined property, north of San Simeon, was used for many family vacations, and it was there William developed a life-long love of the area, particularly a spot called Camp Hill. It was on this 127-acre site beginning in 1919, William started a 28-year collaboration with architect Julia Morgan and built Hearst Castle, a project that continued until 1947 but was never completed. Never completed in William’s mind perhaps, but nevertheless, fully functional, furnished, well lived in, and heavily used for entertaining.

Officially, the castle was called La Cuesta Encantada, Spanish for “The Enchanted Hill.” The buildings totaled 90,000 SF with 42 bedrooms, 61 baths, 19 sitting rooms, and movie theater; while the 127 acres boasted gardens, outdoor and indoor swimming pools, tennis courts, an airfield, and the world’s largest privately-owned zoo at that time. Cost estimates vary because of the unclear accounting practices used by William. For example, he frequently used unaccounted money from his businesses to purchase his treasured furnishings. Estimates range between $7.2 and $10 M (not in today’s dollars) for both construction and contents. At the final accounting in 1945, Morgan brokedown the construction costs alone at $4.717 M. Strangely, Morgan reportedly made only $100,000 profit from the Hearst collaboration; however, she was highly successful beyond Hearst Castle (her mosty famous project). During her career, she designed over 800 buildings and profited handsomely with commissions following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

From the ground, it was difficult if not impossible to see the entire 68,500 SF main house called Casa Grande.

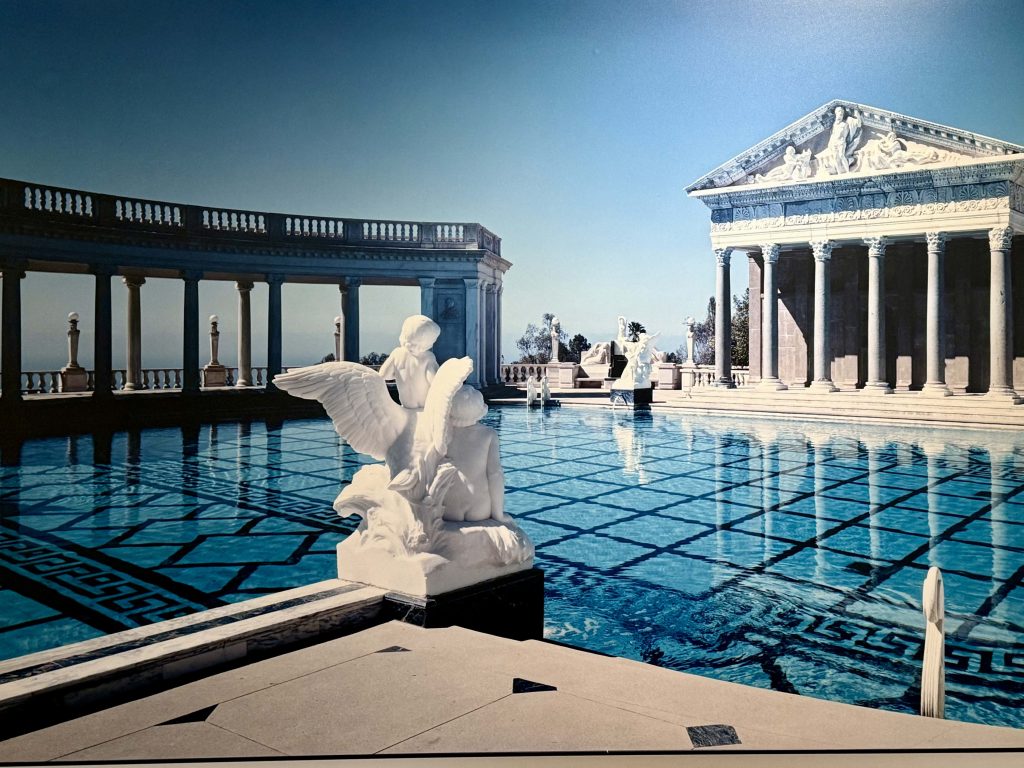

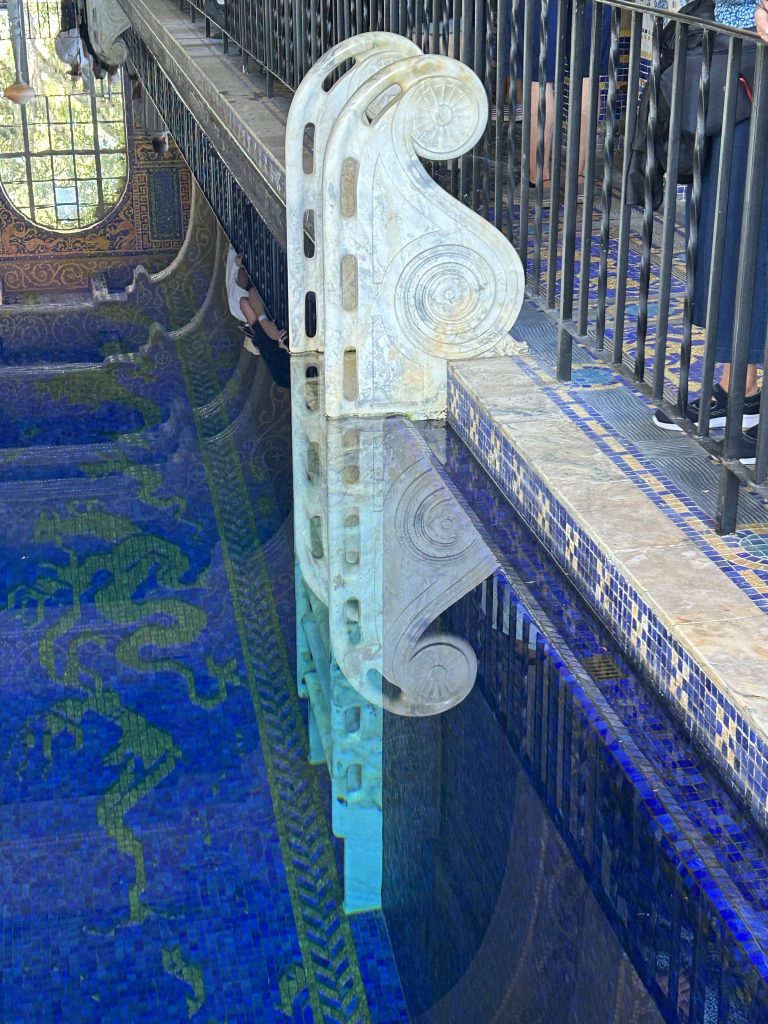

We took a 3-mile bus ride narrated by Alex Trebek from the Visitor Center to the tour-drop off point just below the North Terrace. Our docent was waiting for us and immediately escorted us up a stairway to the Neptune Pool. He gave us a flavor of what kind of client William was for both his architect and construction manger, by relating that the pool we saw was built three times before William was close to being satisfied. It was never fully finished because of William’s persistent design changes and the financial difficulties he experienced between the 1930’s depression and WW II.

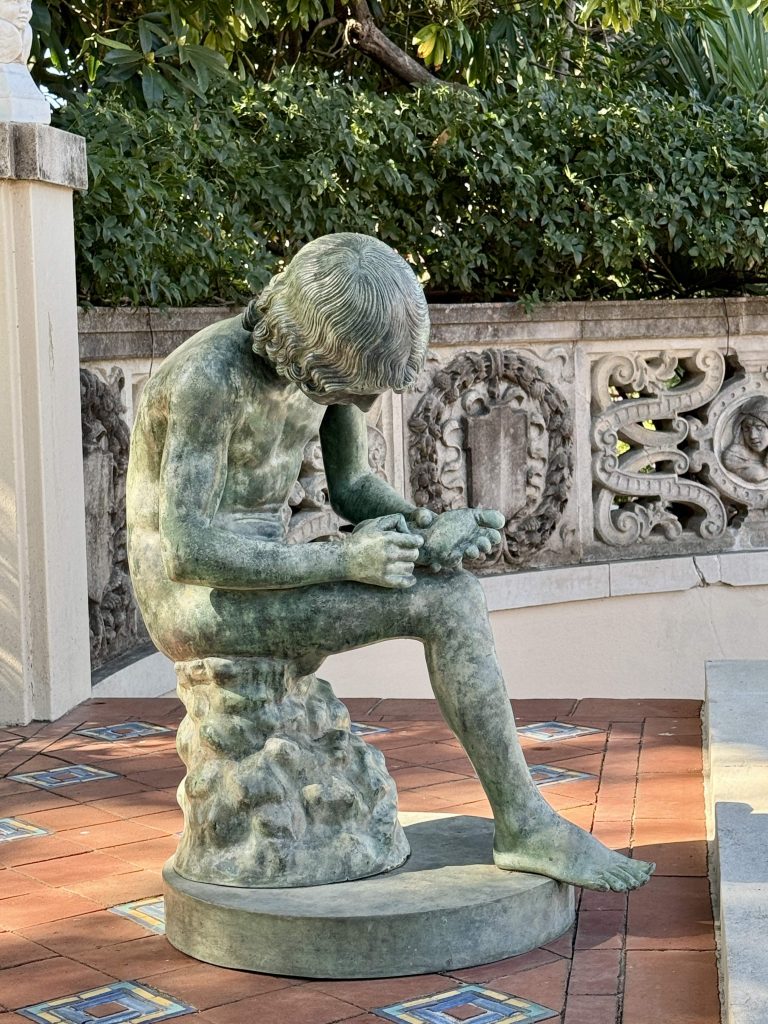

Going forward, I’ve included for each location visited, several overall area or room shots followed by photos of details that interested us. The types of details were landscaping, art pieces, furnishings, carpets, ceilings, and textures. Here were the detail photos for the Neptune Pool.

Some details of the pool deck area and views.

Stairs lead upward from the pool to the bathhouse, terraces, and three guest houses. Our docent claimed Hearst suffered from “terrace envy,” and this original North Terrace, now a subterranean area beneath today’s North Terrace, was set up to demonstrate for tourists the type of material and color boards used by Hearst and Morgan to help make design decisions.

We next visited the bathhouse located between the Neptune Pool and the three guest houses. Definitely a step back to an earlier time and culture. Can you picture both men and women wandering around in long one-piece swimsuits with broad horizontal stripes?

There were three guest houses between Casa Grande and the Neptune Pool. Visiting couples were accommodated with two bedrooms; because at that time, men and women, even if married, slept apart. These lodgings were more spacious that guest rooms in Casa Grande and likely were reserved for the more prominent guests. Guests that included friends and family, but also a host of movie stars, well-to-do businessmen, politicians, and world leaders. We walked up the west side of Casa del Mar, the largest of the three at 5,350 SF and toured inside the other two: Casa del Monte at 2,550 SF and Casa del Sol at 3,620 SF.

Each guest house had two bedrooms with private baths, a common lounge/sitting area, and a terrace facing downhill to the west and northwest.

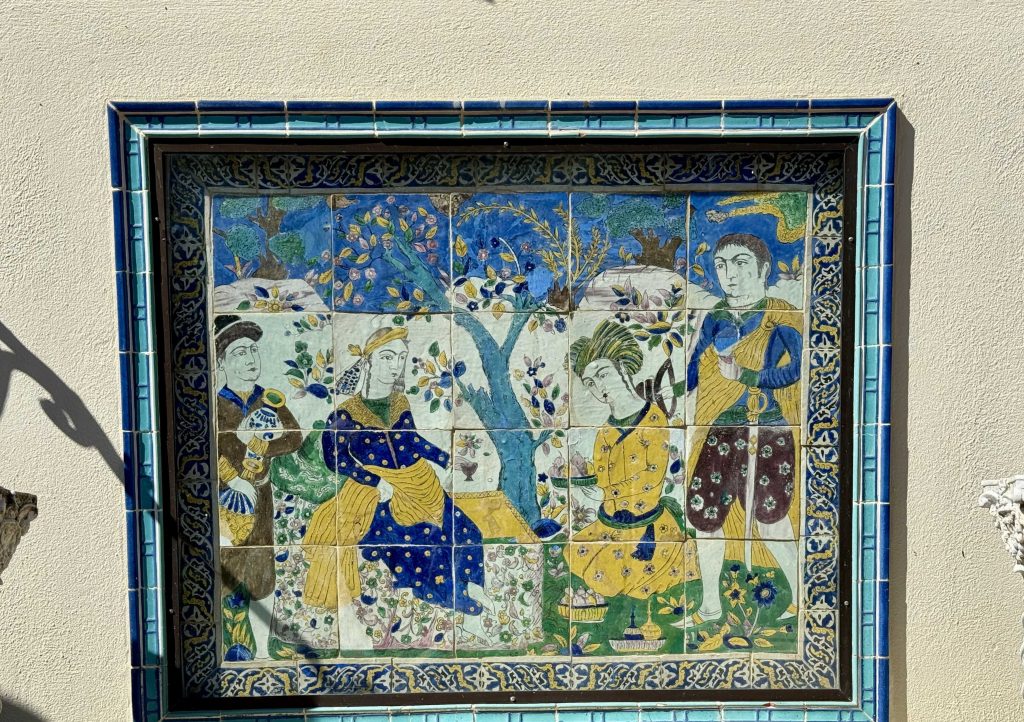

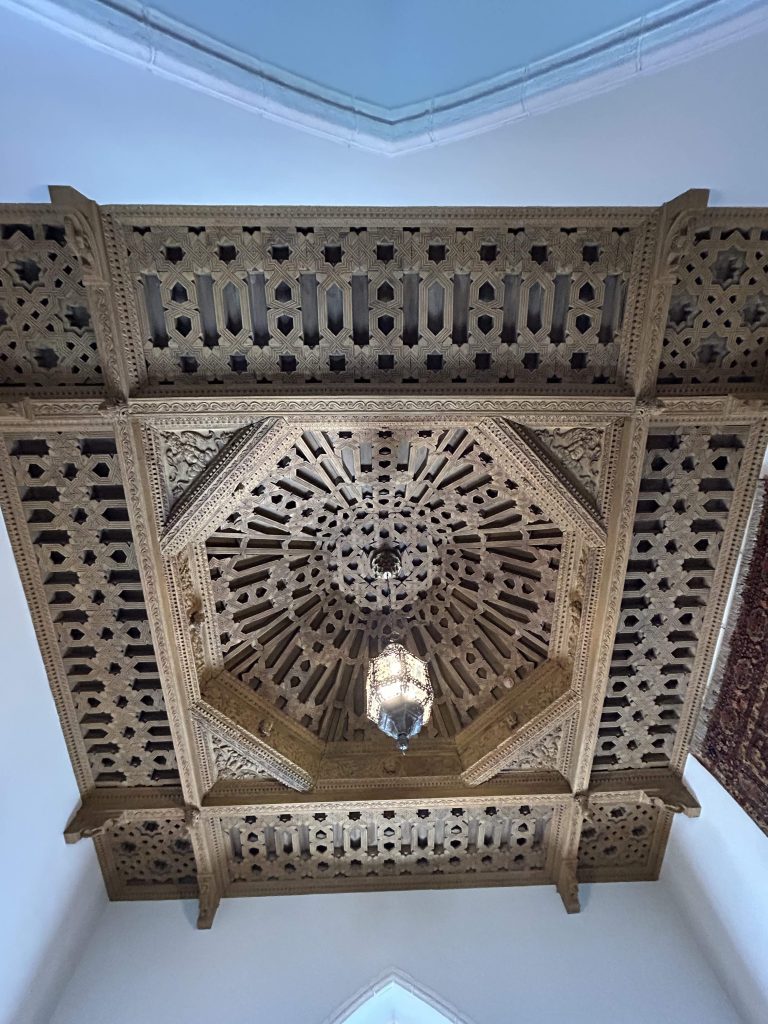

And here were some of the guest house details.

Before entering the main house, we strolled across the North Terrace much as Hearst’s guests might have done, enjoying the view, chatting about the decorations, and wondering what was in store.

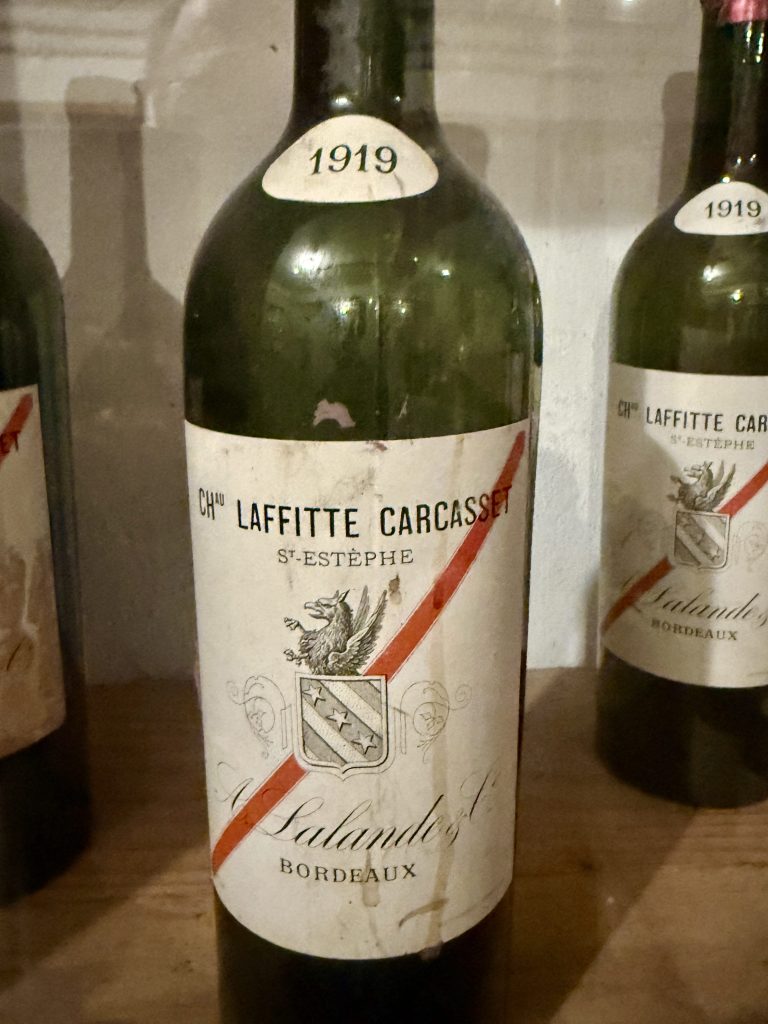

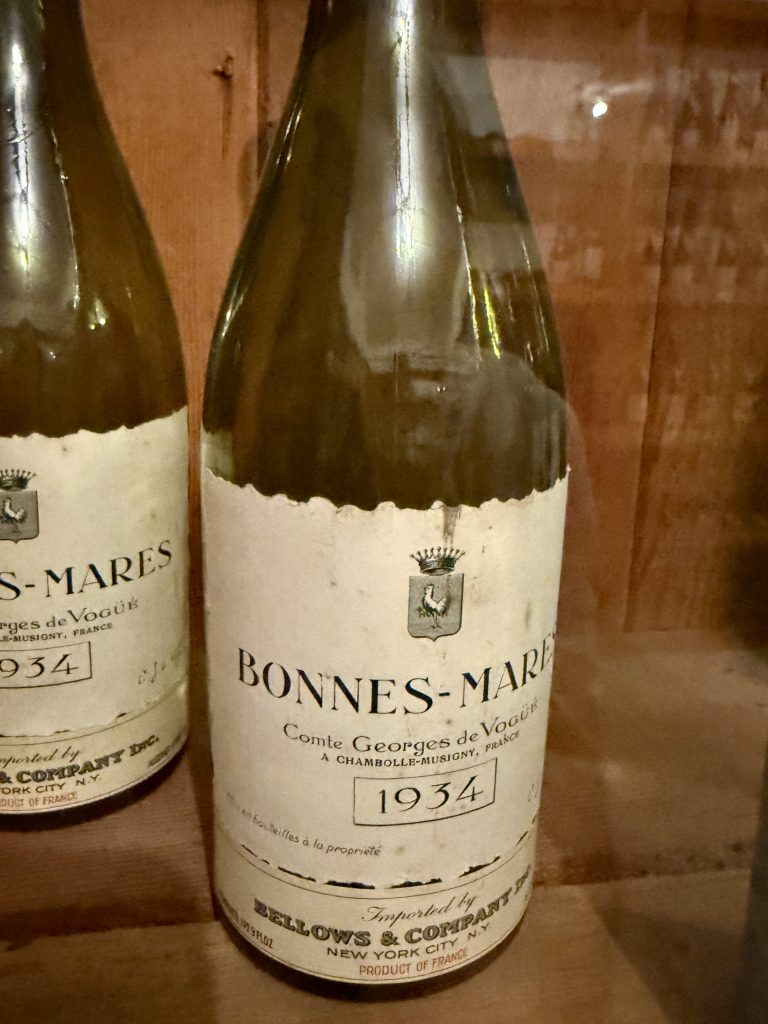

We enjoyed visiting the wine cellar first in Casa Grande. In its heyday, the cellar held 9,000 bottles of imported wine, champagne, sparkling water, and other hard liquors. These imports came from around the world via New York City.

Hearst’s guests paid nothing for their stay; however, William expected conformance to the strict schedule and set of rules he established. Of course there was plenty of free time for swimming, playing tennis, trail riding, hiking, and just plain relaxing, but you best be on time for meals and your required attendance for movies in the theater. On the day of arrival, all guests were required to meet in the waiting hall to be received and welcomed by the host and get instructions on the schedule and rules for their stay.

We were led to the Refectory, where guests were wined and dined, and subsequently to the kitchen. We learned from our docent that the strange-looking chairs along the Refectory walls were called “mercy seats,” which allowed serving staff a leaning respite during lengthy meal events. There was also a dining area in the kitchen for staff, which reminded us of “Downton Abbey” scenes of the help eating together. I wondered if William required the staff to wear uniforms, until I saw examples hanging above the staff dining table.

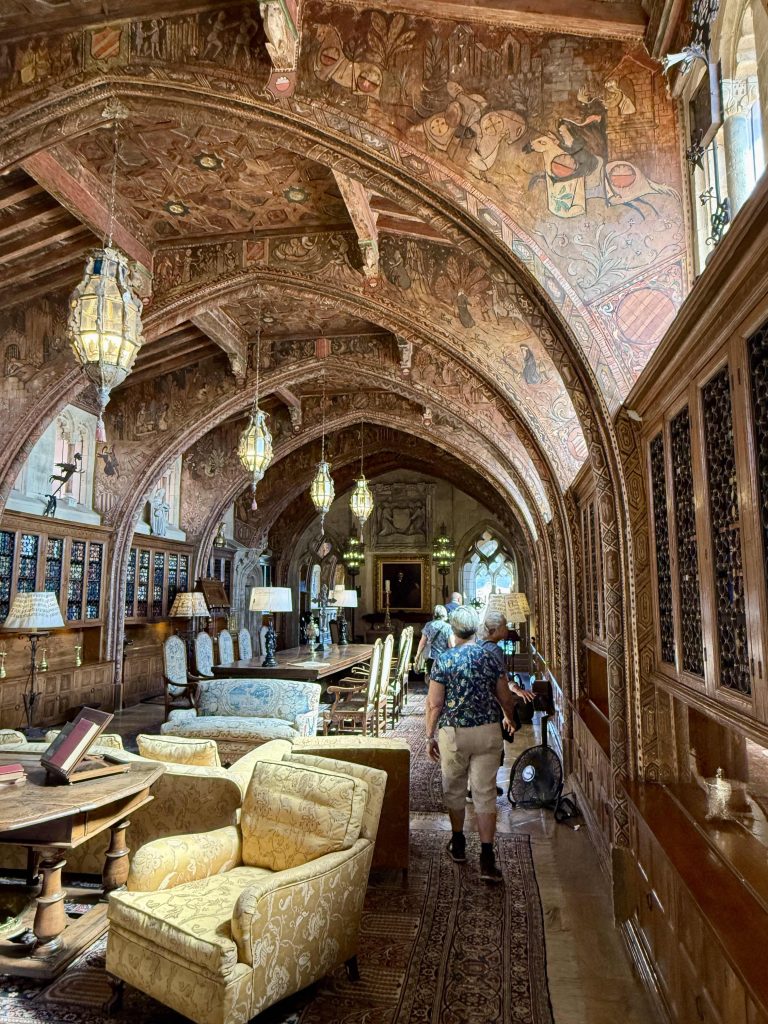

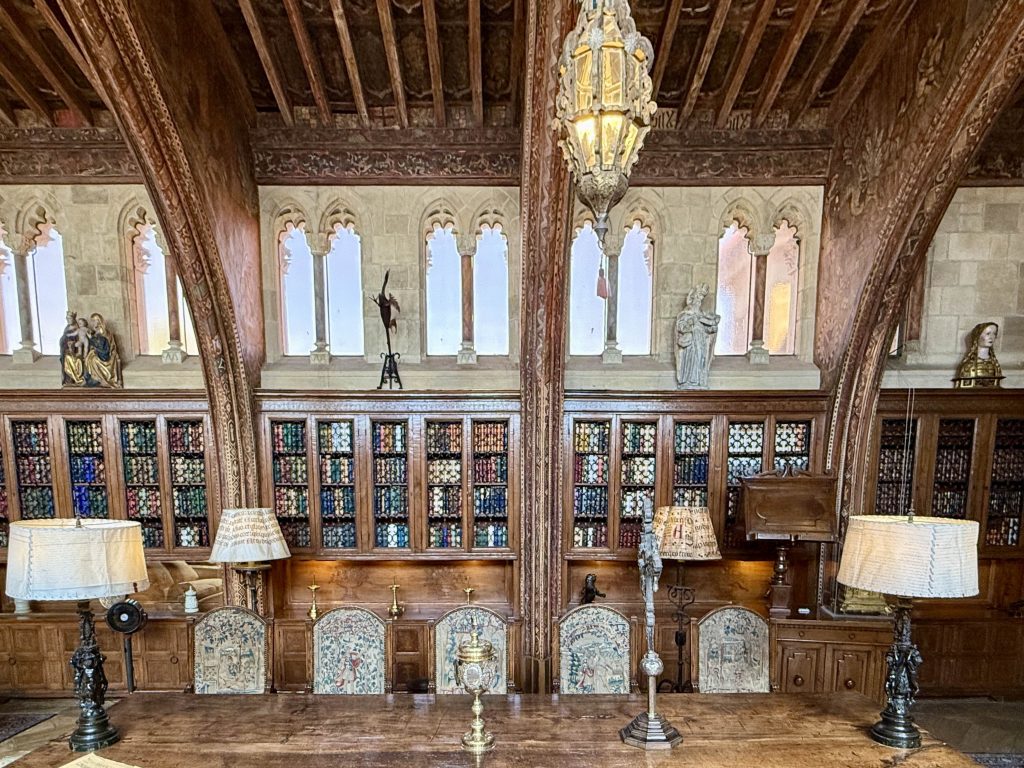

Before entering the library, we passed through a number of lounges, each containing so many volumes of books, we mistakenly thought they might have been the library.

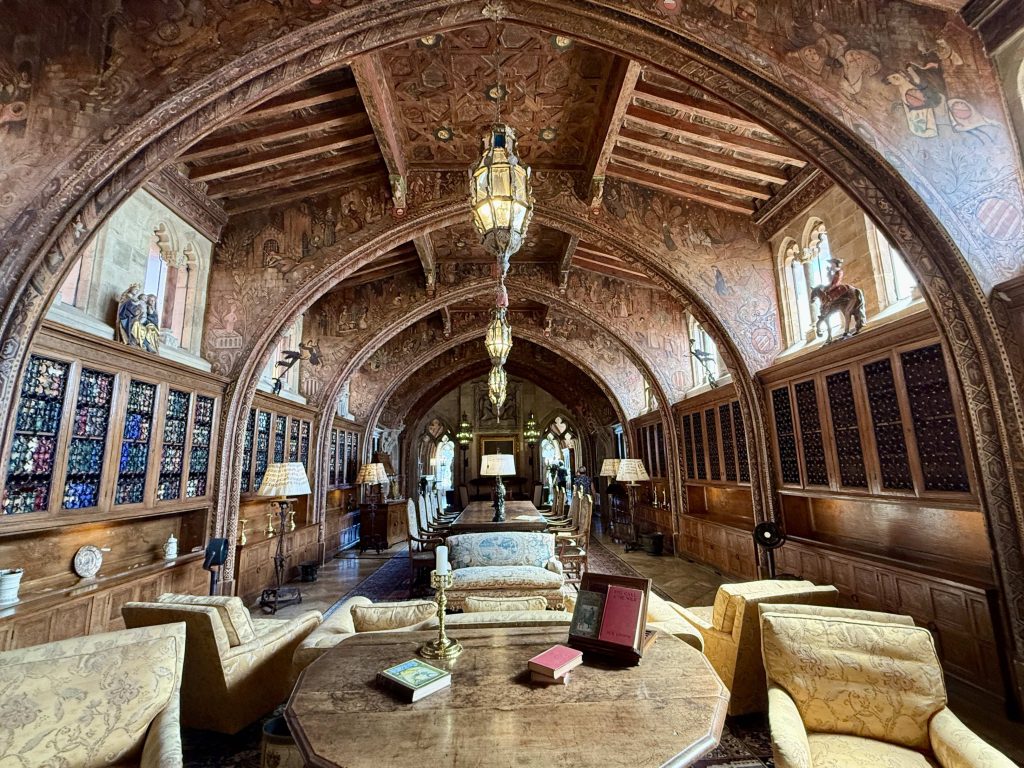

Silly us. The library was unmistakable at 80 feet long, held over 4,000 books, and displayed 150 Greek vases among many other interesting details, such as hand-painted wood trim.

Despite my certainty over having taken pictures of Julia Morgan’s suite and William’s bedroom and sitting area, I couldn’t confirm from all my pictures what was what. Apologies if I’m wrong, but I think this was Morgan’s bedroom. She rarely stayed at Casa Grande.

I did not have a picture of William’s bedroom; however, I did photograph his sitting room and bathroom, and for some strange reason, captured his closets.

Before leaving the house, we toured a second bedroom, bath, and lounge area built for William when he fell into poor health. The intent was to provide him with an isolated and private area where he could be cared for discretely while enjoying a view of the place he loved. He left the Castle without ever staying in the new bedroom and died in Beverly Hills shortly thereafter.

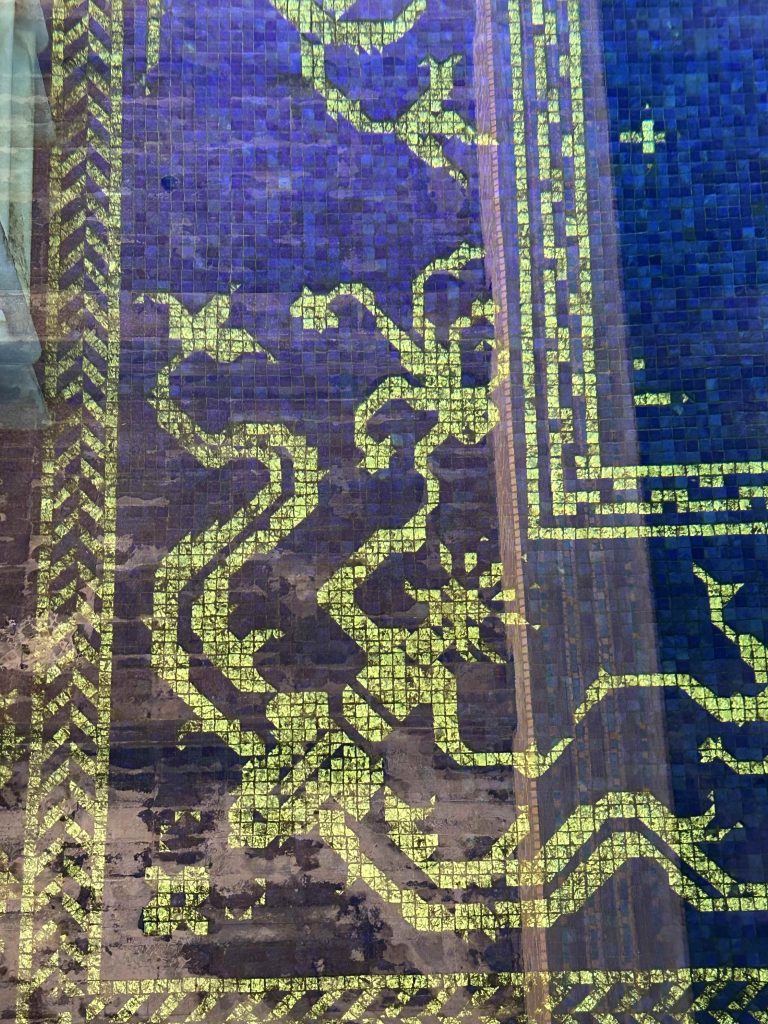

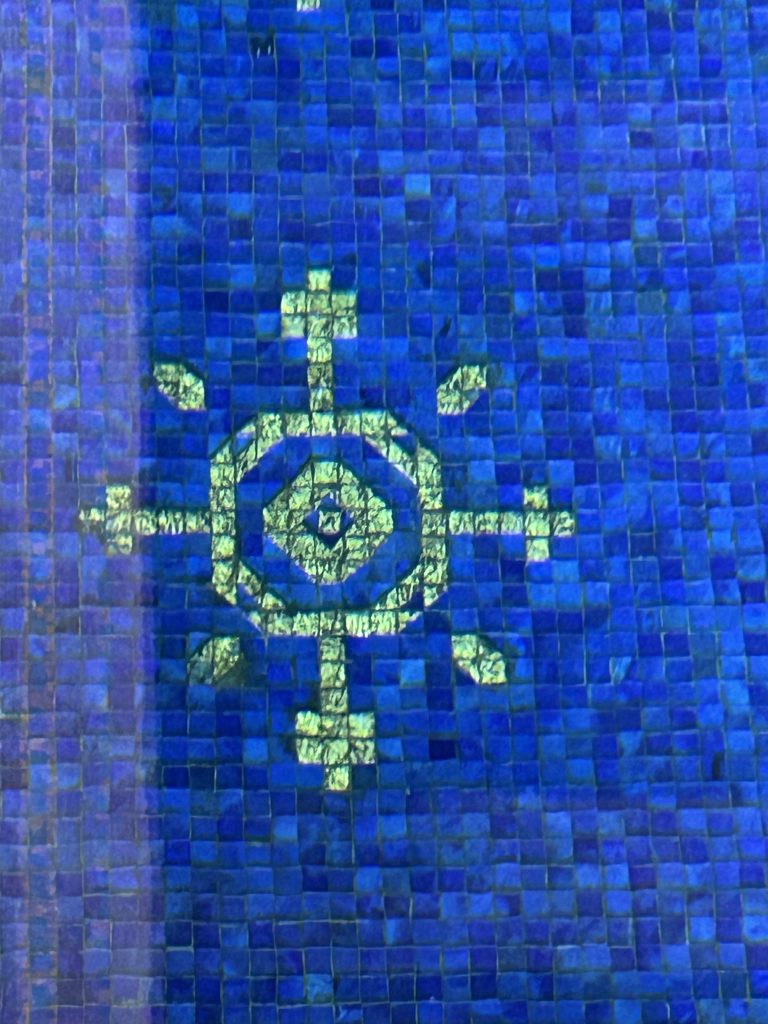

We left Casa Grande, passed the tennis courts, and ended our tour at the extravagant indoor Roman Pool built beneath the courts. The pool design was inspired by the Baths of Caracalla in Rome and the incredible tile work was patterned after the 5th Century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy. It took nearly 2 million, handmade 1-inch square glass tiles colored with blues, orange and gold leaf to complete the pool. The shimmering effects created by the tile mosaics in the pool, on the deck, and up the walls were stunning.

About 700,000 tourists visit Hearst Castle annually, and as a result, they provide thirteen different tours not including those privately organized. While most tours ran $35 per person, we opted for the Julia Morgan Tour at $110/per person because it covered most of the Castle and highlighted Julia Morgan’s collaboration with Hearst. This blog has focused only on the pictures of what we saw rather than the incredible lives led by Hearst and Morgan. Fortunately, our docent covered a wealth of details on their lives, but there was so much, we simply couldn’t remember enough for a credible and coherent narrative here. That said, we strongly recommend if you are in the area, you tour the Castle. Well worth the cost in our opinion.